Think of an art history periods timeline as a grand, unfolding map of human creativity. It's a visual story that takes us from the very first marks made on cave walls all the way to the digital art being created today. This timeline organizes millennia of artistic expression into distinct periods, making it easier to see how styles, techniques, and ideas evolved.

This guide is your personal tour through that incredible story.

How to Read the Art History Timeline

Welcome! You're about to embark on a journey through the history of human creativity. Forget dry lists of dates and names; think of this as an interconnected narrative. We'll start at the very beginning with ancient cave paintings and travel all the way to the boundary-pushing art of our time.

Consider this a highlight reel of our greatest visual achievements. Each period is its own chapter, filled with unique characters, styles, and innovations. You'll discover how major social changes, new inventions, and cultural shifts directly influenced what artists made and why they made it.

Understanding the Flow of Art History

Art rarely appears in a vacuum. It’s more like a conversation that spans centuries. An 18th-century Neoclassical painter, for example, was deliberately looking back to the ideals of Ancient Rome. A 20th-century Cubist, on the other hand, was actively tearing down the rules of realism established during the Renaissance.

Our timeline connects these dots, showing you how one movement inspired, challenged, or simply grew out of another. To make sense of this rich, complex tapestry, we'll focus on a few key things:

- Key Characteristics: What makes a style instantly recognizable? Think of the deep, dramatic shadows in a Baroque painting or the quick, visible brushstrokes of Impressionism.

- Cultural Context: What was going on in the world at the time? We’ll look at how everything from religion and politics to new technologies shaped what artists were doing.

- Pioneering Artists: Who were the trailblazers that defined their eras? We'll get to know the geniuses, from Michelangelo to Monet, who changed the game.

This journey is about more than just memorizing names and dates. It's about developing an eye for art—a kind of visual literacy that helps you understand not just the artwork, but the world that created it.

When you start to see these connections, the bigger picture comes into focus. You begin to understand why art changed and how those shifts help us define what is historical significance. This isn't just about looking at objects in a museum; it's about uncovering vital clues to our shared human story.

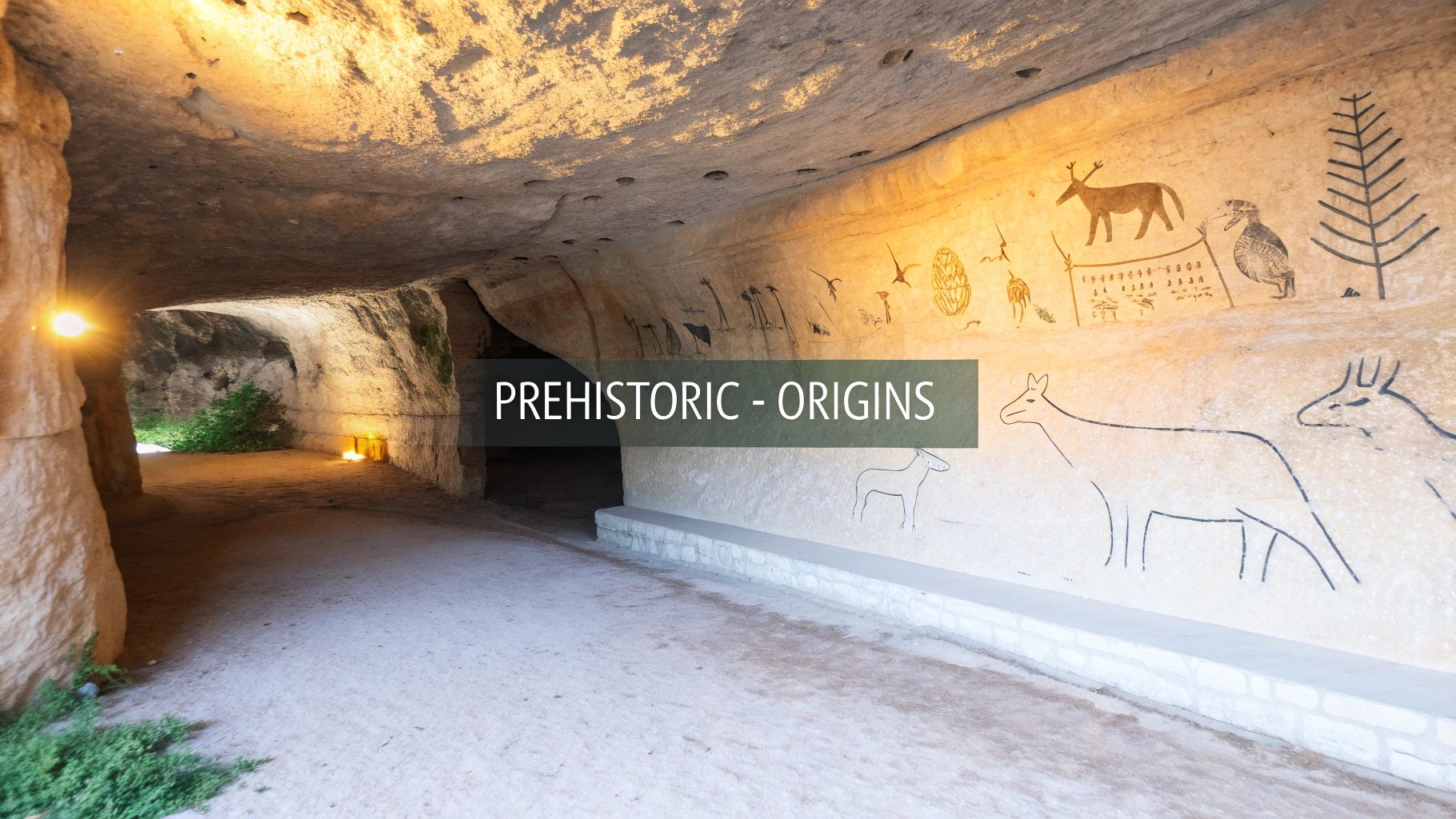

The Dawn of Art: From Caves to Civilizations

Our journey through art history doesn't start in a pristine gallery. It begins deep inside the earth, in caves where the first human artists left their mark tens of thousands of years ago. Long before anyone had invented writing, people were using images to tell stories, record their world, and maybe even connect with the spiritual. This first creative spark ignited during the Stone Age (c. 40,000–4,000 BC), giving us some of history’s most powerful and mysterious art.

You’ve probably seen pictures of the famous cave paintings at Lascaux in France. These aren't just simple doodles; they are breathtakingly sophisticated portraits of bison, horses, and deer, brought to life with natural pigments on rough stone walls. What were they for? That’s the big question, and experts still debate it.

Were these paintings a kind of ritual magic to ensure a successful hunt? Were they the world’s first history books, recounting great triumphs? Or were they part of sacred ceremonies held in the darkness? We may never know for sure, but they reveal a fundamental human drive to interpret the world and leave something of ourselves behind.

From Survival to Society

As people began to shift from hunting and gathering to farming and building villages, their art changed right along with them. You can see this evolution in the small, portable sculptures that started appearing. The most famous of these is the Venus of Willendorf, a tiny limestone figure carved around 30,000 BC.

With her exaggerated features, she obviously wasn't meant to be a realistic portrait of a specific person. Most scholars believe she was a symbol of fertility and survival—a really big deal for a small community trying to make it in a tough world. This little statue shows us that art was already being used to express big, abstract ideas, not just to copy what the eye could see.

The move from permanent cave walls to portable objects was a huge leap. Suddenly, art wasn't tied to one place. It could be carried, traded, and woven into the fabric of daily life, mirroring how human society itself was becoming more complex.

From these ancient beginnings, art was about to take on a whole new job description with the rise of the first great civilizations. It was about to become a tool for power, order, and the quest for immortality.

Art for Gods, Kings, and the Afterlife

In the fertile lands of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt (starting around c. 3500 BC), art became grand, organized, and completely tied up with religion and royalty. While Mesopotamian art often focused on dramatic stories of powerful rulers and their gods, Egyptian art developed a unique style that was obsessed with one thing: eternity.

For nearly 3,000 years, Egyptian artists followed a strict set of rules called the canon of proportions. This was basically a guidebook on how to draw everything, especially people. The result was a consistent, orderly look that barely changed for centuries.

This wasn't because they lacked creativity. It was a conscious choice that reflected their core beliefs about life, death, and the cosmos. Here are a few hallmarks of their style:

- Composite View: You'll notice figures are shown with their head in profile, but their eye and torso face forward. The idea was to show each part of the body as clearly as possible, making the person whole and ready for the afterlife.

- Hierarchical Scale: Size really mattered. Pharaohs and gods were always drawn much larger than everyone else, leaving no doubt about who was in charge.

- Symbolic Colors: Artists chose colors for their meaning, not for realism. Green meant new life, red stood for vitality, and black represented the rich, fertile soil of the Nile that made life possible.

Just look at the treasures found in Tutankhamun's tomb. His brilliant gold death mask wasn't just a fancy portrait; it was a divine vessel for his soul. Every single object was beautifully crafted to serve a purpose on his journey into the great beyond. This era cemented art's role as a way to reinforce social order, document religious beliefs, and try to cheat death itself, paving the way for the classical world that would follow.

Classical Ideals and Medieval Spirituality

After the ancient world laid the groundwork, the story of art takes a sharp turn, heading into two completely different eras that forged the soul of Western culture. First, we have the world of Ancient Greece and Rome (c. 800 BC–476 AD), a time when art was all about celebrating humanity. Everything revolved around ideas like rational order, the pursuit of ideal beauty, and a deep-seated humanism.

This was a period dedicated to perfecting the human form in sculpture and designing buildings that radiated balance and harmony. Art was a public affair, a powerful statement meant to glorify mankind and the state itself.

But then, with the fall of the Roman Empire, everything changed. As Europe entered the Medieval period (c. 500–1400 AD), the very purpose of art was reimagined. The spotlight swung from human perfection to the service of the Christian faith. For a thousand years, art became a powerful tool—a way to teach biblical stories to a population that mostly couldn't read and to glorify God, not man.

Greek Perfection and Roman Power

Our journey into Classical art really kicks off in Greece, where sculpture went through an incredible transformation. The early Archaic statues were pretty stiff and formal, echoing their Egyptian influences. But over centuries, they blossomed into the stunningly lifelike and emotional figures of the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Greek artists became absolute masters of anatomy, carving stone into figures that felt like they could breathe and move.

You can see this evolution play out in stages:

- Archaic Period: Think of the rigid "kouros" figures, with their iconic, almost formulaic smiles and bolt-upright posture.

- Classical Period: This is where artists cracked the code for naturalism. They introduced contrapposto—that relaxed, S-curved stance—which instantly made figures feel more grounded and real.

- Hellenistic Period: Things got even more dramatic. This final phase pushed the emotional boundaries, depicting raw feeling, intense action, and even the unvarnished realities of old age.

The Romans looked at Greek art with tremendous admiration and quickly adapted it to fit their own needs. While the Greeks were chasing an abstract, philosophical ideal of beauty, the Romans were far more pragmatic. They used art as a form of powerful propaganda. Think of the hyper-realistic portraits of emperors designed to project authority, or massive architectural feats like the Colosseum built to scream "imperial might." The intricate bronze statues from this time were a marvel of their engineering and artistry. If you're curious about just how they did it, our guide on how bronze statues are made offers a fascinating look into the complex craftsmanship involved.

The shift from Greek idealism to Roman realism is a perfect example of how art reflects a culture's core values. For the Greeks, art was about perfecting humanity; for the Romans, it was about ruling it.

This entire focus on human achievement and worldly power would all but disappear with the fall of Rome, clearing the way for a profoundly different, spiritual mission for art.

Medieval Art and the Glory of God

With Rome in the rearview mirror, Medieval art turned its gaze inward and upward. The obsessive, detailed realism of the classical world was set aside in favor of symbolism and raw spiritual expression. Making something look real wasn't the point anymore; conveying a divine message was.

The Byzantine Empire, which carried the torch for Rome in the east, created stunning icons and mosaics. Their figures were often flat and elongated, set against shimmering gold backgrounds. This wasn't a lack of skill—it was a deliberate choice to create an otherworldly atmosphere, lifting the scene out of everyday reality.

Meanwhile, in Western Europe, two major styles came to define the era:

- Romanesque (c. 1000–1200 AD): This style feels solid and grounded. Romanesque churches are known for their thick, heavy walls, rounded arches, and small windows, giving them an almost fortress-like feel. The sculpture and art inside were symbolic and stylized, not naturalistic.

- Gothic (c. 1100–1400 AD): The Gothic style was a genuine breakthrough. Architects figured out how to use pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, which let them build impossibly tall cathedrals with walls of massive stained-glass windows. These buildings were conceived as "sermons in stone," designed to flood the space with colored light and pull every visitor's gaze toward the heavens.

This long chapter of art history shows a dramatic pendulum swing—from art made for the glory of man to art made exclusively for the glory of God. It was a stark contrast that perfectly set the stage for the explosive "rebirth" of humanism that was just around the corner: the Renaissance.

The Renaissance and the Rebirth of Humanism

After the long, devout centuries of the Medieval era, something incredible began to happen. The Renaissance (c. 1300–1600) wasn't just a new chapter in art; it was a total cultural reset. The name itself means "rebirth," which is exactly what it felt like—a rediscovery of the art, ideas, and human-focused worldview of ancient Greece and Rome. The spotlight shifted from the heavens back down to earth, right onto people.

This explosion of creativity kicked off in Italy, with Florence as its white-hot center. The engine driving this change was Humanism, a way of thinking that celebrated what people could achieve through their own intellect and skill. For the first time in ages, artists weren't just seen as anonymous craftsmen; they were hailed as geniuses and visionaries, and their place in society changed for good.

A Revolution in Realism

The most obvious shift in Renaissance art is the stunning new sense of realism. Artists became obsessed with making their work look real—as if you could step right into the canvas. To pull this off, they developed some truly groundbreaking techniques.

The biggest game-changer was linear perspective. This was a mathematical system that allowed artists to create a convincing illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. All of a sudden, paintings had real depth, with buildings stretching into the distance and people standing firmly on the ground.

Artists also perfected other methods to breathe life into their subjects:

- Sfumato: Leonardo da Vinci was the master of this. It’s a technique of blending colors and tones so softly that you can’t see any harsh lines. Think of the subtle, almost mysterious smile of the Mona Lisa.

- Chiaroscuro: This is all about using dramatic contrasts between light and shadow. It makes figures and objects look solid and three-dimensional, giving the scene a real jolt of drama.

- Anatomical Study: To paint the body, you have to understand it. Artists like Michelangelo actually studied human anatomy, which is why their figures have such astonishingly accurate muscles and bones.

The Renaissance represents a peak of artistic achievement where technical skill and intellectual curiosity combined to create some of the most iconic works in history. The focus on humanism meant art wasn't just for churches anymore; it was for people.

This creative boom couldn't have happened without money, and a new class of wealthy patrons was eager to spend it. Powerful families like the Medicis in Florence, along with the Papacy in Rome, poured fortunes into art. They commissioned paintings, sculptures, and buildings not just to show their faith, but to broadcast their wealth, power, and sophisticated taste. Because of them, art moved beyond biblical stories to include mythology, historical events, and stunningly personal portraits.

The High Renaissance Masters

The absolute peak of this era, the High Renaissance (roughly 1490–1527), was dominated by three artists who are still household names today: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

- Leonardo da Vinci: He was the quintessential "Renaissance Man." His curiosity was endless, leading him to be a painter, inventor, and scientist. His art, like The Last Supper, is a perfect blend of scientific observation and deep human emotion.

- Michelangelo: A force of nature in sculpture, painting, and architecture. His work is defined by its raw power and emotional weight, from the heroic statue of David to the divine drama on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

- Raphael: If you're looking for harmony and grace, look to Raphael. He perfected a sense of calm, balanced beauty. His masterpiece, The School of Athens, is basically a poster for the Renaissance—a grand celebration of classical thinkers.

The sheer amount of art being made was mind-boggling. In Florence alone, it's estimated that 100,000 altarpieces were painted between 1400 and 1500. This artistic frenzy was supported by busy workshops that trained legions of apprentices, creating the blueprint for the modern art world. You can get a sense of this creative explosion in this overview of Renaissance art periods. The techniques and ideas born in this era became the gold standard for Western art for centuries to come, making it one of the most important stops on our journey through art history.

Baroque Drama and the Age of Revolution

After the calm, measured beauty of the Renaissance, the art world took a sharp, dramatic turn. Artists began chasing intense emotion, over-the-top grandeur, and a feeling of explosive energy. This next chapter on our art history periods timeline covers the turbulent ride from the 17th to the 19th centuries, when art became a powerful mirror for huge shifts in religion and politics. The serene, classical harmony of the High Renaissance was officially over, replaced by something far more theatrical.

This era kicked off with the Baroque period (c. 1600–1750), a style that feels like it’s in constant motion. Born out of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Baroque art was designed to be persuasive and hit you right in the gut. It was meant to pull viewers into biblical scenes with overwhelming drama and awe—a tool to inspire faith and reassert the Church's power through sheer visual force.

The Spectacle of Baroque Art

Imagine walking into a pitch-black room where a single, harsh spotlight illuminates a scene at its most dramatic peak. That’s the essence of Baroque painting. Artists became obsessed with chiaroscuro, a technique that uses extreme contrasts between light and shadow. The Italian painter Caravaggio basically wrote the book on this, using intense, raking light to make his saints and sinners look like real, gritty people caught in moments of crisis.

The effect in sculpture was just as breathtaking. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the undisputed master of the form, could make cold marble look like it was swirling with life. His sculpture The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa isn't a quiet moment of reflection; it’s an explosion of divine passion, with twisting figures and dramatic expressions meant to completely overwhelm you.

Baroque art is the polar opposite of subtle. It’s loud, emotional, and full of movement. It doesn't just want you to see something—it wants you to feel it. This style was a perfect fit for the era's taste for grandeur, whether it was serving God or an absolute king.

As the Baroque style evolved, a lighter, more decorative offshoot emerged, perfectly capturing the lavish tastes of the French aristocracy. It was called Rococo.

From Grandeur to Frivolity in Rococo

The Rococo period (c. 1730–1770) was like the playful, mischievous younger sibling of the Baroque. Where Baroque was heavy and dramatic, Rococo was light, airy, and dripping with ornamentation. It swapped dark, intense theater for pastel colors, swirling S-curves, and scenes of aristocratic romance and fun.

Rococo art felt right at home in the opulent interiors of Parisian salons. Painters like Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher created charming, often flirtatious scenes of wealthy nobles enjoying garden parties and picnics. The key ingredients were:

- A Pastel Palette: Soft pinks, blues, and greens took the place of the dark, somber colors of the Baroque.

- Asymmetrical Designs: Delicate, curving forms snaked their way across everything from paintings to furniture.

- Lighthearted Themes: The subject matter moved away from religious drama and toward love, nature, and the good life.

But this sweet, decorative indulgence couldn't last. As the intellectual ideas of the Enlightenment took hold, people started craving art with more substance, seriousness, and moral backbone.

The Return to Order with Neoclassicism

Pushing back against what they saw as the fluff of Rococo, artists in the Neoclassicism movement (c. 1760–1850) looked to ancient Greece and Rome for a fresh start. New archaeological discoveries, like the unearthing of Pompeii, fueled a passion for order, reason, and civic duty. It was the ideal visual style for a new age of revolution in America and France.

Neoclassical artists were convinced that art should be rational and morally uplifting. The leading voice of this movement was the French painter Jacques-Louis David. His painting Oath of the Horatii became the poster child for the new style, with its crisp, clear composition, severe lines, and powerful message of patriotic sacrifice.

The contrast between these periods is stark. The Baroque used high-voltage emotion to serve faith and monarchy. Rococo captured the carefree elegance of an aristocracy on the verge of extinction. And Neoclassicism provided a stoic, orderly visual language for a new age of reason and revolution. It just goes to show how deeply art is woven into the cultural fabric of its time.

Modern Art: The Great Rebellion Against Tradition

As the 19th century rolled on, a new kind of revolution was brewing—not in the streets, but in the art studios of Europe. For centuries, art had been dictated by powerful academies that demanded historical subjects, idealized figures, and a polished, almost invisible technique. But a growing number of artists started to find these rules stale and disconnected from reality.

They looked at the rapidly changing world around them—the factories, the crowded cities, the everyday people—and decided that was what they should be painting. This seismic shift kicked off the era of Modern Art. It wasn't just one style; it was a cascade of "isms," each movement pushing the boundaries of what art could even be. This part of the art history periods timeline is all about artists finally breaking free and inventing entirely new ways of seeing the world.

The first real crack in the academic wall was Realism. Artists like Gustave Courbet looked at the grand, dramatic scenes of Romanticism and said, "No more." They turned their easels toward the unglamorous, painting common laborers, gritty cityscapes, and quiet, ordinary moments. The goal wasn't to beautify life but to show it exactly as it was.

The Impressionist Revolution

Hot on the heels of Realism came the Impressionists (roughly 1870s–1880s), who took the idea of painting real life in a totally new direction. They weren't just interested in the subject itself; they were obsessed with capturing the fleeting sensation of a moment—the impression it made.

Think of Claude Monet. He wasn't just painting a haystack; he was painting the way the golden afternoon light hit that haystack at 2:37 PM. This obsession with light and atmosphere led to their signature style:

- Quick, Visible Brushstrokes: They used choppy, energetic strokes to capture the immediacy of a scene.

- A Focus on Light: The same subject would be painted over and over again to show how color and form changed with the weather or time of day.

- Painting Outdoors: They packed up their gear and painted en plein air (in the open air) to see these effects firsthand, which was a huge departure from studio work.

The critics were horrified. They called the paintings messy, unfinished, and slapdash. But the Impressionists had fundamentally changed the game. Painting was no longer about creating a perfect, static copy of the world, but about conveying a personal, momentary experience of it.

Moving Beyond the Impression

Of course, the story doesn't end there. A new generation of artists, the Post-Impressionists, saw what the Impressionists were doing and thought it was a great start, but it didn't go far enough. Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne took the brilliant colors and bold brushwork but loaded them with intense emotion and symbolism.

Van Gogh didn't just paint a starry night; he painted the raw, swirling energy and emotion he felt when looking at the sky. For these artists, color and form weren't just for observation—they were tools to express their inner turmoil, joy, and anxieties.

This intensely personal approach cracked open the floodgates for the 20th century. Fauvism came next, cranking up the color dial to eleven with wild, non-realistic palettes meant to convey pure feeling. Then came Cubism, where Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque literally broke down objects into geometric planes, showing them from multiple angles at once. Each step was a more daring leap away from tradition, setting the stage for total abstraction.

Common Questions About Art History Periods

Diving into the art history periods timeline can feel a little overwhelming at first. It’s like learning a whole new vocabulary. To make things clearer, I've put together some simple answers to the questions I hear most often.

Think of this as your quick-start guide. It’s here to clear up any confusion and help you feel more comfortable exploring the incredible world of art.

Art Periods Versus Art Movements

So, what's the real difference between an art period and an art movement? It's a great question.

I like to think of an art period as a major era, a long chapter in history like the Renaissance. It's a broad, overarching style that can define culture for centuries. An art movement, on the other hand, is a much more focused and intense event within that chapter. Movements like Impressionism were often shorter, driven by a tight-knit group of artists pushing back against the old rules and sharing a new vision.

Why Timelines Often Overlap

You've probably noticed that the dates for different periods and movements can get a little messy—they often overlap. That's because art history isn't a neat relay race where one style hands the baton to the next. It’s a slow, organic evolution.

New ideas are always bubbling up while the old ways are still going strong.

You'll find artists working right in the middle of these transitions, creating incredible hybrid works that borrow from both the old and the new. The dates on a timeline just show us when a style hit its peak, not when it suddenly began or ended.

How to Identify Different Art Styles

Telling different art styles apart might seem tough, but it’s a skill you can build with practice. The trick is to start simple. Don’t try to learn everything at once. Just focus on one or two key features for each major period.

- Renaissance: Look for lifelike figures, balanced and symmetrical compositions, and the use of linear perspective to create depth.

- Baroque: This style is all about drama. Expect intense emotion, theatrical scenes, and a powerful contrast between light and shadow (chiaroscuro).

- Impressionism: The giveaway here is the brushwork—quick, visible strokes that capture a fleeting moment and the changing effects of light.

For anyone interested in taking this skill from the museum into the real world, learning how to identify valuable antiques relies heavily on recognizing these historical styles. Even small details, like knowing how to spot bronze foundry marks, can tell you so much about an object's age and story.

Have you ever found an interesting object and wondered about its story? With the Curio app, you can turn that curiosity into knowledge. Just snap a photo, and our app will provide you with the item's history, origin, and an estimated value in seconds. Download Curio today at https://www.curio.app and start uncovering the treasures around you.